The advice here works regardless of what language you are building with (TypeScript, Python, Ruby, whatever) and which AI tool you're using (Cursor, Claude Code, Replit, GitHub Copilot, you name it).

I spent three months letting Claude write code for me without much guidance. The code worked (most of the time). But I often hit a roadblock as soon as I tried to edit code that was previously written. It's as if it was amazing at building a feature one-shot, but then crumbled to iterate on it. The reality is LLMs excel at producing functional code quickly but often default to quick-and-dirty structures that become a nightmare to maintain or extend.

My original thought was: the model isn't powerful enough yet to iterate on existing code. But in reality, the issue often was that it had written the feature in such a way that even a human would have a hard time editing that type of code anyway.

🔍 The Hidden Problem

When you prompt an LLM to "write a function that does X," it focuses on the X, not on how that function fits into a larger system or how easy it will be later on to edit that function.

This is why you get functions that are 200 lines long, classes that do everything, and code that works perfectly until you need to change it. It's a "house of card" type of situation: it stands great at first but collapses quickly as soon as you touch it.

The real skill isn't in writing code that works. It's in writing code that works and can be changed without breaking everything else.

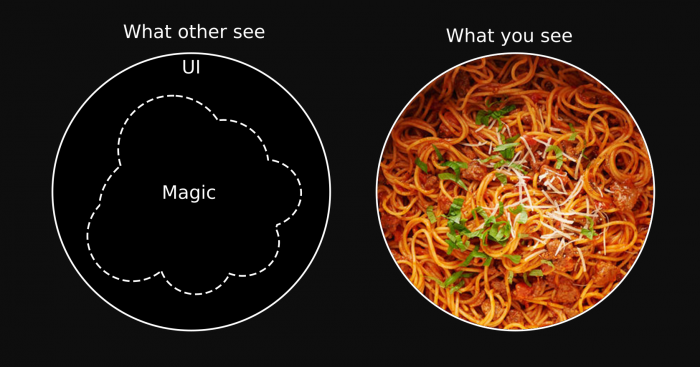

Not so delicious

Not so delicious

🍝 What is Spaghetti Code By The Way?

Spaghetti code is code where everything is tangled together. Change one thing, break three others. Want to reuse a piece of logic? Too bad, it's buried inside a function that does five other things.

The name comes from how it looks when you try to trace the logic, like following a single strand of spaghetti in a bowl of pasta. In short: not fun at all.

Here's a real example I generated with Claude last week (in Python):

def process_user_order(order_id):

# Fetch order

order = db.query("SELECT * FROM orders WHERE id = ?", order_id)

# Calculate total

total = 0

for item in order['items']:

total += item['price'] * item['quantity']

if item['category'] == 'electronics':

total *= 0.9 # 10% discount

# Update inventory

for item in order['items']:

db.query("UPDATE inventory SET quantity = quantity - ? WHERE id = ?",

item['quantity'], item['id'])

# Send email

email_body = f"Your order #{order_id} for ${total} has been processed"

send_email(order['user_email'], email_body)

# Log analytics

analytics.track('order_processed', {'order_id': order_id, 'total': total})

return totalThis function does five different jobs. It's the office worker who handles sales, accounting, inventory, marketing, and customer service. Works great... until you need to change how discounts are calculated, and suddenly you're deep in database queries and email templates.

Because I kept seeing LLMs make such mistakes, I decided to go back to first principle thinking: if LLMs tend to build code that is hard to edit and maintain, then what basic principles exist that can help us prevent that?

📜 The 10 Commandments

I am not a senior engineer, just a tech savvy product guy who happens to know how to code. Those principles are not mine, they are some of the most commonly seen principles of clean code.

1. Single Responsibility & Separation of Concerns

Every function, class, and module should have one reason to change. If you can't explain what something does in one sentence, it's doing too much.

2. Open/Closed Principle

Code should be open for extension but closed for modification. The best code is the code you don't have to change when you add new features.

3. Liskov Substitution Principle

Subtypes should be substitutable for their base types. If you can't swap out an implementation without breaking things, your abstractions are wrong.

4. Interface Segregation Principle

Clients shouldn't depend on interfaces they don't use. Big interfaces are like big classes: they're hard to understand and harder to change.

5. Dependency Inversion Principle

Depend on abstractions, not concretions. High-level modules shouldn't depend on low-level modules. Both should depend on abstractions.

6. High Cohesion, Low Coupling

Things that belong together should be together. Things that don't belong together should be separate. This is the difference between a well-organized toolbox and a junk drawer.

7. DRY – Don't Repeat Yourself

Every piece of knowledge should have a single, unambiguous representation. If you're copying and pasting code, you're copying and pasting bugs.

8. YAGNI – You Aren't Gonna Need It

Don't add functionality until you need it. The best code is the code that doesn't exist. LLMs are incredibly good at adding functionalities you never asked for.

9. Composition over Inheritance

Favor object composition over class inheritance. Inheritance is a powerful tool, but it's also a powerful way to create tightly coupled, hard-to-change code.

10. Law of Demeter

An object should only talk to its immediate friends. If you're chaining method calls like user.getProfile().getSettings().getTheme(), you're violating encapsulation.

Where These Principles Come From

These aren't my ideas. They come from decades of developers (way smarter than I am) making mistakes and learning from them:

- SOLID principles (the first five) were popularized by Robert C. Martin ("Uncle Bob") in the early 2000s. They're the foundation of object-oriented design.

- DRY comes from "The Pragmatic Programmer" by Hunt and Thomas, a true classic in developer land.

- YAGNI emerged from the Extreme Programming movement in the late 90s as a rebellion against over-engineering.

- Composition over Inheritance is a Gang of Four design pattern principle that saved us from inheritance hell.

- Law of Demeter was developed at Northeastern University in the 80s and is basically "don't talk to strangers."

🛡️ Add This as a Rule in Your AI Coding Tool

I tested quite a few variations. This rules / prompts will help your AI avoid writing spaghetti code in the first place.

How to Add It

In Cursor: Add this to your .cursorrules file in your project root.

In Windsurf: Add this to your "Cascade Rules" (Settings → Cascade → Rules).

In Claude Code: Add this to your "Project Instructions" (Project Settings → Instructions).

The Rules

You are a senior software engineer who writes clean, maintainable code.

When writing code, always follow these clean code principles:

- Single Responsibility - Each function/class should have one clear job. If you can't describe it in one sentence without "and", split it.

- Open/Closed - Design code to be extended without modification. Use abstractions and interfaces.

- Liskov Substitution - Implementations should be truly interchangeable. Same inputs/outputs, same behavior contracts.

- Interface Segregation - Don't force code to depend on methods it doesn't use. Keep interfaces focused.

- Dependency Inversion - Depend on abstractions, not concrete implementations.

- High Cohesion, Low Coupling - Keep related things together, unrelated things separate and independent.

- DRY - Don't repeat logic. Extract shared code into reusable functions.

- YAGNI - Only build what's explicitly requested. No "might need this later" features.

- Composition over Inheritance - Favor composing behaviors over inheritance hierarchies.

- Law of Demeter - Objects should only talk to immediate friends, not chain through nested objects.

Code quality requirements:

- Functions under 20 lines when possible

- Clear, descriptive naming (no clever abbreviations)

- Favor explicit over clever

- No deep nesting (max 2-3 levels)

Before implementing, briefly consider if the approach violates any principles. If it does, refactor the design first.

You can adapt those rules to your language / framework and provide concrete examples of good patterns to follow and bad patterns to avoid. This will make your LLM even more likely to follow those rules.

Note: You can also use this as an audit prompt by asking: "Review the code in [file] against these principles and suggest refactoring steps if needed."

The 10 Commandments (With Real Examples)

I am using simplified examples in Python (simple syntax) but those could have been written in any language. They are simplified versions of the types of code I have seen LLMs generate when working on real-life codebases.

🎯 1. Single Responsibility & Separation of Concerns

The Rule: One function, one job. If you can't describe what a function does without using the word "and," it's doing too much.

Real Example:

Bad (what AI can give you by default):

def handle_checkout(user_id, items):

# Validates items, calculates total, processes payment,

# updates inventory, sends confirmation email

pass # 150 lines of tangled logicGood (after applying the principle):

def validate_cart(items): pass

def calculate_total(items): pass

def process_payment(user_id, total): pass

def update_inventory(items): pass

def send_confirmation(user_id, order_id): pass

def handle_checkout(user_id, items):

validate_cart(items)

total = calculate_total(items)

payment = process_payment(user_id, total)

update_inventory(items)

send_confirmation(user_id, payment.order_id)Why will it save your life?

When payment processing breaks, you know exactly where to look. When you need to change how totals are calculated, you don't risk breaking email confirmations.

🔓 2. Open/Closed Principle

The Rule: You should be able to add new features without modifying existing code.

Real Example:

I asked Claude to build a discount system. First version:

def apply_discount(price, user_type):

if user_type == 'student':

return price * 0.9

elif user_type == 'senior':

return price * 0.85

elif user_type == 'military':

return price * 0.8

return priceEvery new discount type means editing this function. That's nest for future bugs.

Better version:

class Discount:

def apply(self, price): pass

class StudentDiscount(Discount):

def apply(self, price): return price * 0.9

class SeniorDiscount(Discount):

def apply(self, price): return price * 0.85

def apply_discount(price, discount: Discount):

return discount.apply(price)Now I can add a VIP discount without touching existing code. It just works.

🔄 3. Liskov Substitution Principle

The Rule: If you swap out a piece of code with a different implementation, it shouldn't break things.

Real Example:

Let's say I need to add multiple payment methods to a checkout system. AI could write something like...

class CreditCardPayment:

def process(self, amount):

# Processes payment

return True # Returns boolean

class PayPalPayment:

def process(self, amount):

# Processes payment

return {"transaction_id": "12345", "status": "completed"} # Returns dict!

# In checkout code:

def checkout(payment_method, amount):

result = payment_method.process(amount)

if result: # This works for CreditCard but breaks for PayPal!

print("Payment successful")See the problem? CreditCard returns True/False, PayPal returns a dictionary. Code expecting a boolean breaks when you swap to PayPal.

Fixed version:

class PaymentMethod:

def process(self, amount) -> bool:

"""Process payment and return True if successful"""

pass

class CreditCardPayment(PaymentMethod):

def process(self, amount) -> bool:

# Process credit card

return True

class PayPalPayment(PaymentMethod):

def process(self, amount) -> bool:

# Process PayPal

result = paypal_api.charge(amount)

return result["status"] == "completed"

# Now checkout works with any payment method:

def checkout(payment_method, amount):

if payment_method.process(amount):

print("Payment successful")Now you can swap between CreditCard and PayPal without changing any checkout code. Both always return a boolean.

🔌 4. Interface Segregation Principle

The Rule: Don't force code to depend on methods it doesn't use. Real Example:

Here is an examples of AI-generated code for an interface for content management in an app:

class ContentManager:

def create_post(self): pass

def edit_post(self): pass

def delete_post(self): pass

def publish_post(self): pass

def unpublish_post(self): pass

def moderate_comments(self): pass

def ban_user(self): pass

def view_analytics(self): passA regular user only needs create/edit. But they have to implement or ignore 6 other methods. That's messy.

Better:

class PostEditor:

def create_post(self): pass

def edit_post(self): pass

class PostPublisher:

def publish_post(self): pass

def unpublish_post(self): pass

class Moderator:

def moderate_comments(self): pass

def ban_user(self): passNow each role gets only what it needs.

🔄 5. Dependency Inversion Principle

The Rule: Your main code shouldn't depend on specific implementations. Both should depend on interfaces.

Real Example:

Here is a bad version Claude gave me for a notification feature in an app:

class EmailService:

def send(self, to, subject, body):

# Uses SendGrid specifically

sendgrid.send_email(to, subject, body)

class UserNotifier:

def __init__(self):

self.email = EmailService() # Locked into EmailService

def notify(self, user, message):

self.email.send(user.email, "Notification", message)If I want to add SMS notifications, now I have to rewrite UserNotifier. Or at least my AI will have to and is very likely to get confused and break logic in the process.

Better version:

class NotificationService:

def send(self, recipient, message): pass

class EmailService(NotificationService):

def send(self, recipient, message):

sendgrid.send_email(recipient, "Notification", message)

class SMSService(NotificationService):

def send(self, recipient, message):

twilio.send_sms(recipient, message)

class UserNotifier:

def __init__(self, service: NotificationService):

self.service = service # Works with any service

def notify(self, user, message):

self.service.send(user.contact, message)Now I can swap email for SMS without touching UserNotifier.

🧩 6. High Cohesion, Low Coupling

The Rule: Related things should be together. Unrelated things should be separate and independent.

Real Example:

I asked for a user authentication system and got:

# user.py

class User:

def __init__(self, username, email):

self.username = username

self.email = email

self.db = DatabaseConnection() # Why is User dealing with databases?

def save(self):

self.db.execute("INSERT INTO users...") # And validation?

def validate_email(self):

# Email validation logic here

def send_welcome_email(self):

# Email sending logic here - this is completely different!Low cohesion: User, database, validation, and email sending are all mixed.

Better:

# user.py

class User:

def __init__(self, username, email):

self.username = username

self.email = email

# user_repository.py

class UserRepository:

def save(self, user: User): pass

# validators.py

class EmailValidator:

def validate(self, email): pass

# email_service.py

class WelcomeEmailer:

def send(self, user: User): passHigh cohesion: Each module has one clear purpose. Low coupling: They don't depend on each other's internals.

🔂 7. DRY – Don't Repeat Yourself

The Rule: If you're copying code, you're copying potential bugs.

Real Example:

Claude generated this for different user roles:

def get_admin_dashboard():

user = authenticate(request)

if not user: return redirect('/login')

if user.role != 'admin': return error(403)

data = fetch_admin_data()

return render('dashboard', data)

def get_manager_dashboard():

user = authenticate(request)

if not user: return redirect('/login')

if user.role != 'manager': return error(403)

data = fetch_manager_data()

return render('dashboard', data)

def get_user_dashboard():

user = authenticate(request)

if not user: return redirect('/login')

data = fetch_user_data()

return render('dashboard', data)Three copies of authentication logic. Bug in auth? Fix it three times.

Better:

def require_auth(required_role=None):

def decorator(func):

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

user = authenticate(request)

if not user: return redirect('/login')

if required_role and user.role != required_role:

return error(403)

return func(user, *args, **kwargs)

return wrapper

return decorator

@require_auth('admin')

def get_admin_dashboard(user):

data = fetch_admin_data()

return render('dashboard', data)

@require_auth('manager')

def get_manager_dashboard(user):

data = fetch_manager_data()

return render('dashboard', data)

@require_auth()

def get_user_dashboard(user):

data = fetch_user_data()

return render('dashboard', data)One auth implementation. One place to fix bugs and to test.

🚫 8. YAGNI – You Aren't Gonna Need It

The Rule: Don't build features you don't need yet.

LLMs are particularly bad at this. Unless specifically told about what not to do, they will tend to add unnecessary logic because all it does is pattern matching with its training dataset.

I asked Claude for a simple user settings page. It gave me:

class UserSettings:

def __init__(self):

self.theme = 'light'

self.language = 'en'

self.timezone = 'UTC'

self.notifications_email = True

self.notifications_sms = False

self.notifications_push = False

self.privacy_show_email = False

self.privacy_show_phone = False

self.privacy_searchable = True

self.advanced_api_key = None

self.advanced_webhook_url = None

# ... 15 more fields I never asked forI only needed theme and language. The rest was "we might need this later."

Better:

class UserSettings:

def __init__(self):

self.theme = 'light'

self.language = 'en'Add fields when you actually need them. Not before. Less surface area for bugs and headaches down the line.

🎹 9. Composition over Inheritance

The Rule: Instead of inheriting behavior, compose objects that have the behaviors you need.

Real Example:

Let's say you are building user roles for a project management SaaS. Started with inheritance:

class User:

def view_projects(self): pass

class Editor(User):

def edit_projects(self): pass

class Admin(Editor):

def delete_projects(self): pass

def manage_users(self): pass

# Problem: Need a "Project Manager" who can edit and manage users but NOT delete

# Can't extend Admin (includes delete). Can't extend Editor (missing manage_users).

# Inheritance tree is too rigid!Better with composition:

class User:

def __init__(self, email):

self.email = email

self.permissions = set()

def grant(self, *permissions):

self.permissions.update(permissions)

def can(self, permission):

return permission in self.permissions

# Now create any combination:

editor = User('editor@company.com')

editor.grant('view_projects', 'edit_projects')

admin = User('admin@company.com')

admin.grant('view_projects', 'edit_projects', 'delete_projects', 'manage_users')

# That impossible role? Easy now:

project_manager = User('pm@company.com')

project_manager.grant('view_projects', 'edit_projects', 'manage_users')

# No 'delete_projects' - perfect!Let's say sales needs a custom role for an enterprise client, you just compose the exact permissions they need. No inheritance gymnastics.

👥 10. Law of Demeter

The Rule: Don't dig through nested objects. Talk to your direct friends only.

Real Example:

Claude's first attempt:

def display_user_theme(user):

theme = user.getProfile().getSettings().getTheme()

return f"Theme: {theme}"This assumes User has a Profile, Profile has Settings, Settings has Theme. Change any of that structure, and this breaks.

Better:

# In User class

class User:

def get_theme(self):

return self.profile.settings.theme # User handles its own structure

# Now the function is simple

def display_user_theme(user):

theme = user.get_theme()

return f"Theme: {theme}"The function only talks to User. User handles its own internal structure. Change the structure? Only User code changes.

💡 Bottom Line

I'm not saying you need perfect code. I'm saying you need code you can change without breaking things.

These principles aren't about being clever or academic. They're about saving your future self from the hell of debugging spaghetti code.

Your AI will write exactly what you ask for. So ask for better code.

The idea is to give it the guardrails that senior developers use instinctively.

Give it a try.

Written with ❤️ by a human (still)