Vibe Coding is the Punk Rock of Software

— Rick Rubin —

Punk rock looked like chaos, but the best bands had rules. Three chords, two minutes, no solos.

I've spent $3,000+ in tokens and 600+ hours coding with LLMs, building production features in days instead of weeks. And I've noticed something: it made us lazy. We stopped thinking about how to code well. We type prompts, hit enter, get working apps. When it fails, we blame the model.

After an embarrassing amount of trial and error, I figured four rules to keep me sane in the process. They're nothing revolutionary, they're just engineering principles applied to coding with LLMs.

After all, you would never go to a human engineer and ask: "Hey, just code this feature, will you?". There is no reason why it should be any different with AI.

📋 Rule 1: Define Before You Build

✂️ Rule 2: Divide and Conquer

🧩 Rule 3: Context is King

🧪 Rule 4: Test or Regret

Note: This article focuses on the key principles. For a real deep dive, hands-on recommendations and templates specific to vibe coding with Cursor, see A Practical Guide to Vibe Coding with Cursor

📋 Rule 1: Define Before You Build

Here's a pattern I caught myself doing: I'd write "build me x" and hit enter, expecting magic. The LLM would try to read my mind, make 20 assumptions about what I want, and deliver something that "kind of worked".

Here I had done something silly: I had pushed all the specification work onto the model. That's backwards. And I ended up paying the "lazy tax": hours spent debugging mysterious issues, rewriting features that almost worked, explaining over and over: "No, no! Here is what I actually wanted...".

It's like telling a contractor to start building your house without talking to an architect. Halfway through, you decide you want a different bathroom layout. Then an extra bedroom. Then a different roof. Each change is possible, but expensive. The lazy tax compounds.

Why vague prompts fail: LLMs are exceptional at pattern completion, but not at mind reading. A vague prompt like "build me a todo app" forces the model to guess at thousands of unstated requirements: how tasks are organized, what happens during edge cases, how the UI should look like. Every vague requirement multiplies possible interpretations exponentially. The AI makes reasonable assumptions, and some will inevitably be wrong. Clear specifications reduce the solution space from thousands of possibilities to only a few clear paths of implementation.

Good engineers think before they code. They write down requirements. They debate trade-offs. They document decisions. Coding with AI doesn't change this reality.

The good news is you don't have to write the specifications yourself. LLMs actually excel at this part. The key is to engage in a thorough questioning process first, then let the LLM generate the specifications from your answers.

⁉️ The Questioning Process

This step will feel counterintuitive because we're accustomed to asking LLMs questions and receiving answers, not the other way around. But flipping this dynamic is where the real thinking begins. When you prompt the LLM to interrogate your assumptions, you force it to converge on the proper way of thinking about your problem, uncovering blind spots you didn't know existed.

Before jumping to specifications, briefly define what you want to build, and refrain from going into implementation right away! Prompt the LLM to ask you as many questions as possible about edge cases, user scenarios, and technical constraints. This conversation is where the real thinking happens.

I used to skip this step. It felt inefficient. Why spend 20 minutes asking questions when I could just start coding? But I learned that those 20 minutes save hours. The LLM isn't just asking questions; it's mapping the problem.

We'll use the ubiquitous todo app as an example.

The LLM will ask questions like:

"Should tasks be editable after creation?"

"Should there be a limit to the number of characters on a task name?"

"Can a task have multiple owners?"

"Should there be task categories or tags?"

"Do you need offline support?"

...This is where LLMs truly shine: helping you define scope. Their probabilistic nature explores edge cases you hadn't considered, feature interactions you hadn't connected, and failure modes you'd discover in production. They explore possibilities across thousands of similar scenarios, and you choose which paths matter. You're still in the driver's seat, just with a better map.

Answer these questions thoughtfully. The quality of your answers directly determines the quality of the specification that follows. Once you've covered edge cases and critical scenarios, the LLM can generate a comprehensive specification in seconds, complete with user stories, acceptance criteria, and technical requirements. What would take you hours to write manually before, the LLM does in a matter of minutes.

Here's the real beauty: the LLM eliminates the writing part almost entirely, letting you spend 90% of your time thinking and only 10% reviewing. For a complex feature, you might spend 20-30 minutes total, most of that pure thinking. The LLM handles formatting, structure, and clarity. You focus on the hard part: figuring out what you want, while the AI puts it into words.

The hottest new programming language is English

— Andrej Karpathy —

✍️ The Specification Spectrum

Here's what I've learned: there's a spectrum between lazy prompting and full-blown specification documents. On one end, you have "build me a feature" with zero context. On the other end, you have a complete Agile specification with user stories, personas, epics, acceptance criteria, and a full data model.

Neither extreme works well with LLMs in my humble experience.

Lazy prompting forces the LLM to fill in too many blanks, leading to assumptions that don't match your needs.

Over-specification bloats your context window with unnecessary details, causing what's commonly known as context rot where the important information gets lost in the noise. LLMs don't need to know about personas or business alignment the way human teams do. They just need enough context to write good code.

The sweet spot is somewhere in between: define sufficiently to provide the context required for the LLM, but not so much that you overwhelm it with irrelevant information.

Three methodologies have influenced my thinking here:

1. Linear

The issue tracking tool Linear doesn't believe in user stories. They advocate for simply defining what you're building without the ceremony. Instead of "As a user, I want to...", they just describe the feature: "Add ability to filter issues by label." Direct, clear, focused.

2. Jobs To Be Done (JTBD)

The Jobs To Be Done framework emphasizes job stories over user stories. Job stories focus on what the feature does rather than who it's for. The format is:

When [situation], I want to [motivation], so I can [expected outcome]

You can find a great article on this here. That approach is used across some of the fastest growing companies such as Intercom, MailChimp or GitLab. It's nothing new, this was written more than 10 years ago.

This matters because LLMs don't need to understand your target audience the way your marketing team does. Knowing "who" it's for is a business question that helps humans align with each other, but it's not necessarily relevant for writing good code. What matters is the behavior you want.

3. Shape Up

The Shape Up methodology by 37signals (creators of Basecamp and Ruby on Rails) is a really interesting lean approach to building software. Two concepts from this model are really relevant to vibe coding in my opinion:

- defining boundaries (No-Gos)

- rabbit holes.

It's just as important to tell the LLM what NOT to do as it is to tell it what to do.

I've noticed two main ways LLMs go off the rails:

-

They build functionalities you never asked for. Based on their training data, they assume certain functionalities should exist. If you're building a todo app, they might add categories, priorities, and due dates even if you just wanted a simple list.

-

They over-engineer the implementation. They'll reach for complex patterns, add unnecessary abstractions, or build elaborate systems when a simple solution would work.

The way to prevent this is with explicit no-gos and rabbit holes. Create guardrails by being clear about what you don't want: "Don't add authentication," "Don't create a separate API layer," "Keep the data model simple with just a single table."

The Shape Up philosophy is essentially: Be concrete enough to remove ambiguity, but abstract enough to leave room for creativity - and explicitly state boundaries.

✍️ Three Layers of Specification

A good specification covers three dimensions:

- Behavior - The functionalities users need and the results they expect

- Design - What the user experience looks like and feels like

- Technical choices - The key technical decisions behind the architecture of the system

Each layer constrains the others. Your UI can't promise features your data model doesn't support, and your technical choices limit what behaviors are feasible.

File Formats: When documenting specifications for LLMs, stick to two formats:

- Markdown (.md) for human-readable content like user stories, wireframes, and documentation

- JSON (.json) for structured data like acceptance criteria, technical choices, and screen inventories.

These formats are optimized for LLMs to parse and reference—they use fewer tokens than XML or YAML, are easier to generate and validate, and work seamlessly with most AI tools.

🎬 Behavior

As we said earlier, don't over-specify. Focus on the job to be done by your user (why this feature exist in the first place) rather than the persona (business alignment question).

Instead, use job stories to describe what the feature does:

- "When I have items to track, I want to add them to a list, so I can remember them"

- "When I'm done with an item, I want to mark it complete, so I can see my progress"

Keep it simple and focused on behavior, not ceremony.

Acceptance criteria are for edge cases only. You don't need Given/When/Then scenarios for every interaction. Save them for the specific edge cases that matter - the ones that could break in subtle ways or the ones you absolutely need to get right.

Here's when to write acceptance criteria:

- Complex state transitions that need to work exactly right

- Edge cases that have tripped you up before

- Critical flows where failure costs money or locks people out

- Scenarios where the "obvious" implementation is actually wrong

Here's an example for a critical edge case relate to payment - I have run into this edge case on a production app with paying customers:

Scenario: Subscription cancellation takes effect at end of billing period

Given a user has an active monthly subscription that renews on the 15th

And today is March 3rd

And the user has paid for service through March 15th

When the user clicks "Cancel Subscription"

Then the subscription remains active until March 15th

And the user retains full access until March 15th

And the subscription will not renew on March 15th

And the user sees: "Your subscription will end on March 15th"Without this spec, an LLM might cancel access immediately (losing the customer money they already paid) or schedule the cancellation for the wrong date. This is a critical edge case as it relates to payment.

This is worth specifying because it's an edge case the LLM might handle differently than you want. But you don't need acceptance criteria for "user clicks button and modal opens" - that's obvious from the job story, it will consume your precious context window.

The goal is clarity where it counts, not documentation for its own sake. Be explicit about the edge cases that matter. Let the LLM figure out the obvious stuff.

Below a lightweight format for your PRD (Product Requirement Document). It gives the LLM what it needs without the overhead of full Agile / Scrum documentation:

File Formats: Stick to Markdown (.md) for human-readable content and JSON (.json) for structured data. These formats use fewer tokens than XML or YAML and work seamlessly with most AI tools.

Feature Name

Description

[Brief, clear description of what you're building - 2-3 sentences max]

Job Stories

[What the feature does, not who it's for]

When [situation], I want to [action], so I can [outcome].

Example:

- When I have multiple tasks to track, I want to add them to a list, so I can remember what needs to be done.

- When I complete a task, I want to mark it as done, so I can see my progress.

- When I'm looking at my list, I want to see only incomplete tasks, so I can focus on what's left.

No-Gos

[Explicit boundaries - what's out of scope]

These are features or functionality we're intentionally NOT building to fit the appetite and keep the project focused:

- No user authentication or multi-user support

- No task categories, tags, or labels

- No due dates or priority levels

- No separate API layer or microservices architecture

- No mobile app version (web only)

Rabbit Holes

[Risks and pitfalls to avoid]

These are the ways the implementation could go off the rails or get over-engineered. Be explicit about staying away from these:

- Don't build a complex state management system - keep it simple with local state

- Don't create elaborate data models with multiple tables - one table is enough

- Don't add real-time sync or websockets - standard HTTP requests are fine

- Don't implement undo/redo functionality - that's a rabbit hole we don't need

- Don't optimize for performance at this stage - ship the simple version first

Acceptance Criteria

[Only for important edge cases - not everything needs this]

Use this section sparingly. You don't need acceptance criteria for every behavior, but they're valuable for specific edge cases that are critical and non-obvious. Acceptance criteria translate directly into tests.

Format using Given/When/Then (Gherkin syntax):

- Given [initial state]

- When [action occurs]

- Then [expected result]

Example:

Scenario: Subscription cancellation takes effect at period end

- Given a user has an active monthly subscription renewing on the 15th

- And today is March 3rd

- And the user has paid through March 15th

- When the user cancels their subscription

- Then the subscription remains active until March 15th

- And the user retains full access until March 15th

- And no charge occurs on March 15th

- And the cancellation confirmation shows "Your subscription ends on March 15th"

Scenario: Password reset link expires after use

- Given a user requested a password reset at 2:00 PM

- And successfully changed their password using the link at 2:05 PM

- When the user clicks the same reset link again at 2:10 PM

- Then the link shows as invalid

- And displays "This reset link has already been used"

- And prompts the user to request a new link if needed

Why this format works:

- Job stories explain behavior briefly without unnecessary context about personas

- No-gos and Rabbit Holes prevent feature creep and over-engineering

- Acceptance criteria are reserved for edge cases that matter, making them test-ready

Speaking of tests, acceptance criteria in Given/When/Then format map directly to test cases. This is essentially Behaviour Driven Development (BDD) using the Gherkin language. When you write acceptance criteria this way, you're already halfway to having automated tests. We'll dive deeper into testing in Rule 4.

📐 Design

Specify screens upfront but you don't need to go down to the exact name of each component on it.

The key is to think through the user experience systematically. What screens need to be added, edited, or deleted? How do users navigate through this feature? What interactions are possible on each screen?

Create a screen inventory that maps out:

- New screens - What needs to be built from scratch

- Modified screens - What existing screens need updates

- User flows - How users move through the feature step-by-step

For each screen, describe the layout and key interactions. The goal is to be explicit about what goes where - the LLM shouldn't guess your navigation structure or decide which UI patterns to use.

Breadboarding from Shape Up: Before diving into visual details, use the "breadboarding" technique borrowed from electrical engineering. In electronics, a breadboard is a prototyping tool that lets you wire up circuits quickly without soldering — it has all the components and connections of a real device, but no industrial design or finished casing. You can see how electricity flows through the system without getting distracted by what the final product looks like.

Ryan Singer adapted this concept for software design in the Shape Up methodology. The idea is powerful: by sketching interfaces with words instead of pictures, you stay at the right level of abstraction. You're concrete enough that the LLM understands the flow and structure, but abstract enough that you're not making premature design decisions about colors, edges, or exact pixel perfect layouts.

This prevents two common problems:

- spending hours on visual design before you know if the flow even works

- the LLM making assumptions about UI flows when you haven't been explicit

A software breadboard has three key components:

-

Places - These are the locations users can navigate to: screens, pages, dialogs, dropdown menus, modals. Think of these as the "rooms" in your application.

-

Affordances - These are the things users can interact with: buttons, input fields, links, checkboxes, dropdowns. They're the actions available at each place.

-

Connection lines - These show how affordances move users between places. When someone clicks this button, where do they go? What happens when they submit this form?

Use words and simple arrows, not pictures. This is intentional: you want to think about the logic and flow without getting pulled into visual design decisions too early.

Example breadboard for team invitation feature:

[Team Settings Page]

- List of current team members (name, role, email)

- "Invite Member" button → [Invitation Form]

- "Remove" link (for each member) → [Confirmation Dialog]

[Invitation Form]

- Email input field

- Role dropdown (Admin/Member/Viewer options)

- Custom message text area (optional)

- "Send Invitation" button → [Confirmation Toast] → [Team Settings Page]

- "Cancel" link → [Team Settings Page]

[Confirmation Dialog]

- "Are you sure you want to remove [Name]?"

- "Remove" button → [Team Settings Page]

- "Cancel" button → [Team Settings Page]

[Confirmation Toast]

- "Invitation sent to [email]"

- Auto-dismisses after 3 seconds

Notice how this captures all the essential interactions and flows without specifying button colors, exact placement, or typography. The LLM now knows exactly what needs to exist and how it connects, but still has room to make good design decisions within those constraints.

You can provide Figma designs for each screen, but unless you're a UX/UI designer, building those takes significant time. If you want to move fast, ASCII wireframes are a perfect middle ground: they're text-based layouts that LLMs can easily understand and reference, use fewer tokens than visual tools for LLMs to produce, and let you iterate in seconds without any design software.

This aligns very well with the idea of "fat marker" in the Shape-Up methodology: visual sketches with such broad strokes that adding details is impossible. Just enough for the LLM to not go completely rogue, but not so much that you have to spend hours designing it.

Example ASCII wireframe for the team invitation page:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ ← Back to Team Settings [Save & Exit] │

│ │

│ Invite Team Members │

│ ──────────────────────── │

│ │

│ Email Address │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ user@company.com │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ Role │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Member ▼ │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ Custom Message (Optional) │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Welcome to our team! Looking forward│ │

│ │ to working with you. │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ [Send Invitation] [Cancel] │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────┘This upfront design work prevents the LLM from making assumptions about your UI or user flows and ensures the feature fits naturally into your existing application.

🏗️ Technical choices

Don't let the LLM default to what's common. Have the conversation first. For instance: "What are the trade-offs between WebSockets, Server-Sent Events, and polling?". Make the LLM explain options, not just pick one during the implementation phase.

Lack of planning is how you get spaghetti code.

Technical choices fall into three main categories:

1. Libraries/SDKs - Services you install in your codebase

Examples:

- Email services: SendGrid vs AWS SES vs Resend

- Authentication: Auth0 vs Clerk vs Supabase Auth

- Form validation: Zod vs Yup vs Joi

- PDF generation: jsPDF vs PDFKit vs Puppeteer

2. Third-party APIs - HTTP endpoints you call directly

Examples:

- Payment processing: Stripe vs PayPal vs Square

- File storage: AWS S3 vs Cloudinary vs UploadThing

- Analytics: PostHog vs Mixpanel vs Amplitude

- AI services: OpenAI vs Anthropic vs Google AI

3. Technical Architecture - How your feature works under the hood

Examples:

- Data model: Schema design, relationships, indexing strategy

- Component structure: How modules/components interact

- Security model: Authentication, authorization, permission checks

- Error handling: How errors propagate and are displayed

For each choice, have the LLM explain:

- Pros and cons of each option

- Integration complexity with your existing stack

- Performance trade-offs you should consider

- Security implications of each approach

- Cost implications at different scales

Example conversation:

"For real-time notifications in our task assignment feature, what are the options between WebSockets, Server-Sent Events, and polling? What are the trade-offs for a team of 10-50 users?"

The LLM should explain that WebSockets offer bidirectional communication but require connection management, Server-Sent Events are simpler for one-way communication but have browser limitations, and polling is simple but inefficient. Then you can make an informed decision based on your specific needs.

This upfront technical discussion prevents the LLM from defaulting to the most common solution (which might not be the best for your use case) and ensures you understand the implications of each choice before committing to implementation.

Documenting Technical Choices

Once you've had these conversations with the LLM, document the decisions in a structured format. Here's an example of how to structure your technical choices into a JSON file:

Documenting Technical Choices

Once you've had these conversations with the LLM, document the decisions in a simple, readable format. Keep it light—you're not writing a formal architecture document, just capturing the key trade-offs so the LLM understands your constraints.

Example: Real-time notifications for a SaaS dashboard

We need to show users live updates when their background jobs complete. Here are the options we considered:

Option 1: Polling (Simple HTTP requests every few seconds)**

- ✅ Dead simple to implement - just a setInterval

- ✅ Works everywhere, no special server setup

- ✅ Easy to debug with browser dev tools

- ❌ Wastes bandwidth checking when nothing changed

- ❌ Not truly real-time (2-5 second delay)

- Decision: Good enough for v1 ✓

Option 2: Server-Sent Events (SSE)**

- ✅ True real-time updates

- ✅ Automatic reconnection built-in

- ✅ One-way is fine for notifications

- ❌ Requires keeping connections open

- ❌ Can hit browser connection limits

- Decision: Consider for v2 if polling becomes a problem

Option 3: WebSockets**

- ✅ Full bidirectional communication

- ✅ Lowest latency

- ❌ Overkill for one-way notifications

- ❌ More complex infrastructure (connection management, load balancing)

- ❌ Harder to debug

- Decision: Not needed for this use case

Final choice: Start with polling. It's the simplest solution that works, and we can always upgrade to SSE later if users complain about the delay. Don't over-engineer it.

Keep your technical choices documentation this lightweight. The goal is to prevent the LLM from choosing something overly complex when a simple solution works fine—or from choosing something too simple when you actually need the complexity.

🔄 The Rise of Spec-Driven Development

This emphasis on defining specifications before building has recently gained momentum under the banner of "spec-driven development" (defined by the folks at GitHub). The idea is focused on creating machine-executable specifications to guide AI code generation. Several open-source projects now support this approach:

- Spec Kit by GitHub provides a toolkit for AI-powered spec-driven development.

- OpenSpec offers a lightweight framework for defining machine-executable interaction specifications.

- BMAD-METHOD delivers an agile AI-driven development framework (much heavier, wouldn't recommend for solo devs or small teams).

I've also been working on my own system: SpecWright (open-source, GitHub). The key difference from the tools above is that SpecWright provides a full web UI experience that guides you through building entire specifications before you write any code.

What makes it unique:

- Guided process — It leads you through a specific spec-building workflow step by step

- Linear-inspired UX/UI — A sleek, modern interface for managing your specifications

- Direct AI coding tool integration — Instead of putting your own API key, you use whatever AI coding tool you already have (Cursor, Claude Code, etc.). The web app handles automation by injecting the right prompt at the right time with the relevant context window

- Spec preview — A clean UI to preview and refine your specifications before generating code

For a deeper dive into this emerging methodology, see GitHub's article on spec-driven development with AI.

✂️ Rule 2: Divide and Conquer

The first time I asked an LLM to build an entire feature in one shot — data model, migrations, backend, API, frontend, all of it — I thought I was being efficient. I wasn't. I was asking it to juggle too much context. It ended up hallucinating, contradicting itself, forgetting things it wrote three steps prior. It's like asking someone to cook dinner while fixing your plumbing while filing your taxes. Sure, they might be capable of all three. But not at the same time, and definitely not while remembering you're allergic to shellfish.

The solution is simple: break it down.

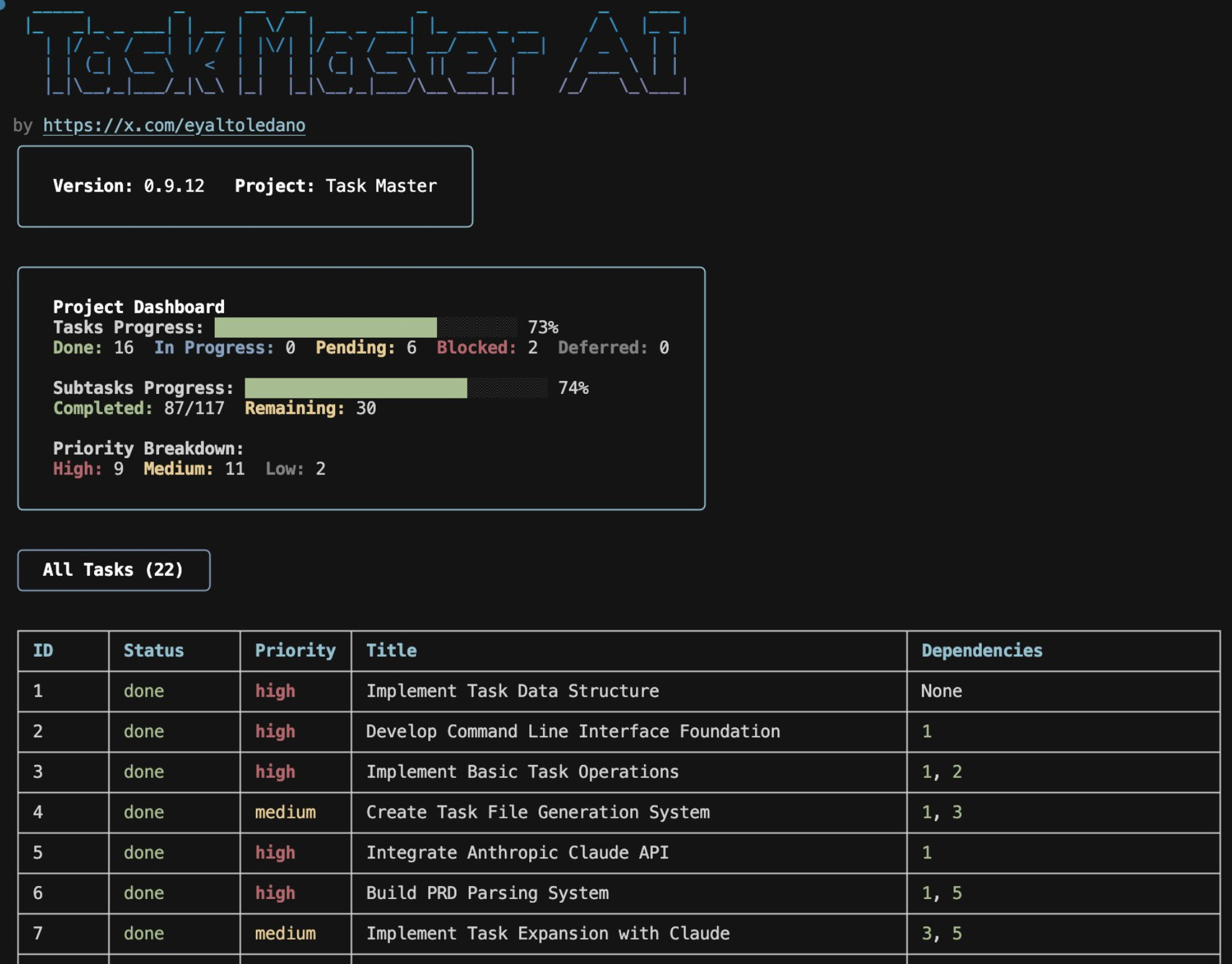

Some open-source projects like TaskMaster (22k+ stars on GitHub) do a bunch of heavy lifting for you. I've used it and been impressed by it.

TaskMaster CLI interface

TaskMaster CLI interface

But you can also do it yourself with a simple prompt and a logical sequence:

-

Data model first. Define your schema. What tables, what fields, what relationships. Get this right because everything builds on it.

-

Service layer. Any external API connections, authentication flows, third-party integrations. Isolate these early.

-

Backend logic. Following something like MVC (Model, View, Controller), implement your controllers, your business logic, your data access layer.

-

Frontend last. Once the data model exists and the backend works, building the UI is just wiring things up.

-

Testing strategy. Write integration tests for critical paths - authentication, payments, data exports, anything that would cost money or lose trust if it breaks (more on testing in Rule 4).

Breaking things down forces clarity. If you skip to the UI before figuring out your data model, you'll rebuild it twice: once without constraints, once when you discover what the database can actually read and update. Your UI needs to reflect what's possible with your data layer, and building it first means designing in a vacuum. Each step validates the one before it.

🧩 Rule 3: Context is King

Modern AI coding tools like Cursor, Claude Code, or Lovable are good at understanding your existing codebase — they use RAG (Retrieval Augmented Generation) to convert your code into embeddings, finding relevant files across your project. But there's context they can't see, and that's where you come in.

There are 3 main categories of context you need to provide to your LLM:

- 📚 Keep it current → documentation

- 🔍 Show the symptoms → logs

- 👁️ Give it eyes → visual feedback

Note: Anthropic recently published an interesting article on context engineering, exploring how managing context has evolved beyond traditional prompt engineering. While prompt engineering focuses on crafting the right instructions, context engineering addresses the broader challenge of curating and managing the entire set of information (context) available to LLMs at any given time.

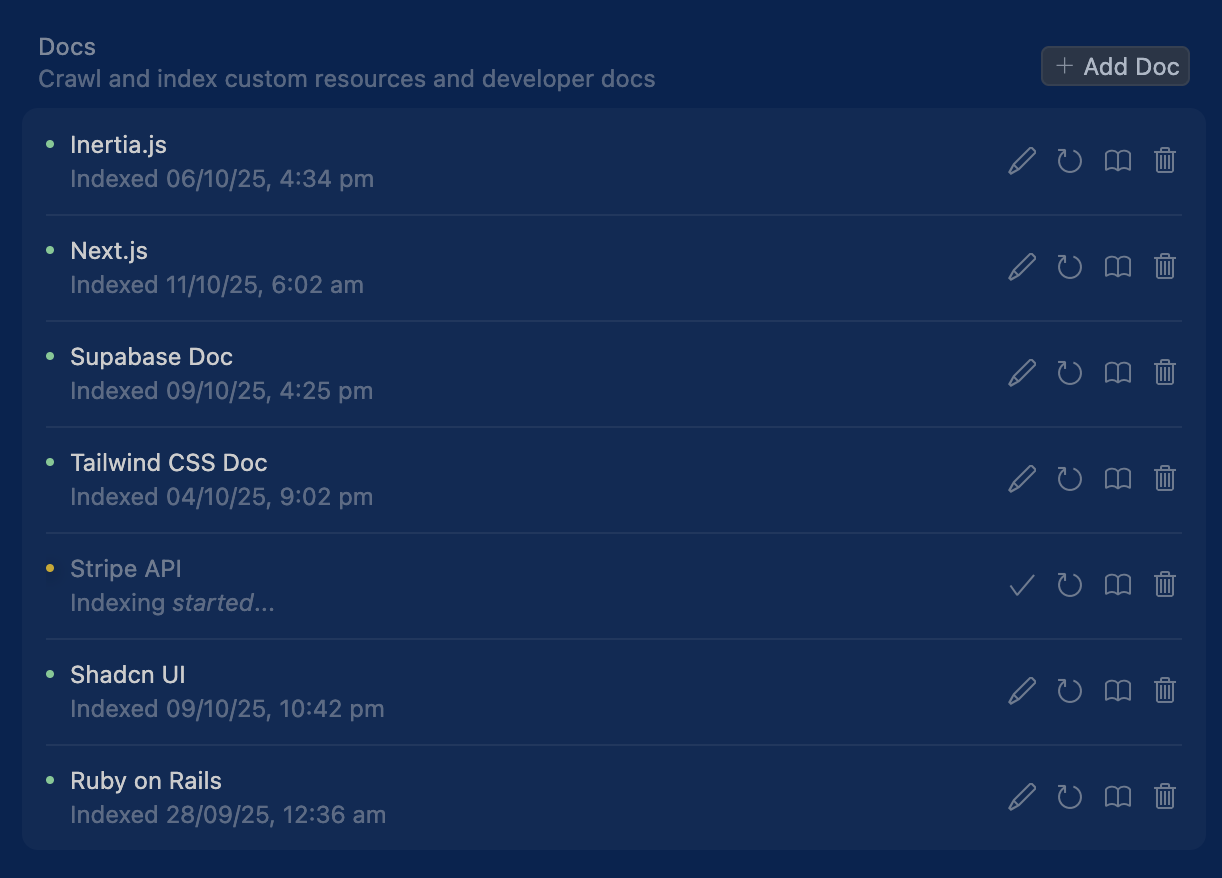

📚 Documentation

I learned this the hard way. LLMs are trained on data from months or years ago — frozen in time, like a developer who went into a coma in 2023. That Stripe API endpoint? Changed. That React hook? Deprecated. That library you're using? Released a new version with breaking changes. Don't trust the training data. Pull the actual docs, API references, library READMEs, migration guides, etc, and feed them to the LLM. Make it work from current information, not memory.

The docs indexing settings in Cursor

The docs indexing settings in Cursor

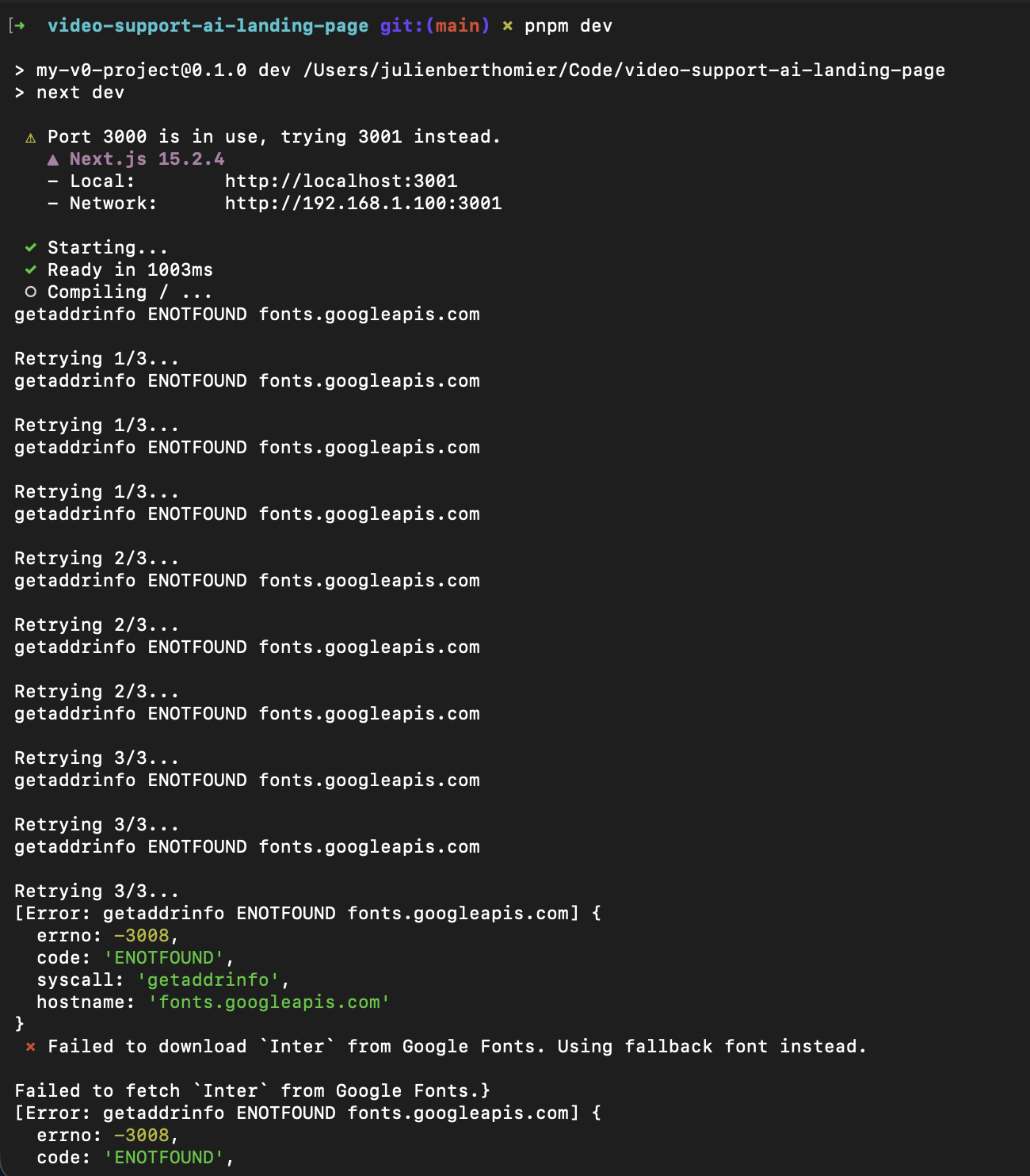

🔍 Logs

Debugging isn’t a side quest, it’s half of software development. Studies and industry surveys have shown that engineers spend between 35% and 50% of their time debugging and fixing issues. That means if you don’t get good at debugging with an LLM, you’re wasting half its potential. Treat it like pairing with another engineer: feed it logs, stack traces, and context, and it’ll often get you to the root cause faster than you could alone.

You can't say "this doesn't work, fix it" to an LLM any more than you can say that to a human engineer without getting a death stare. Show the error. Console logs for frontend issues, server logs for backend issues. The exact error message, the stack trace, and the specific behavior that triggered it. When those aren't enough, prompt the LLM to add more debugging steps, extra print statements, additional logging, or specific checks to isolate the problem.

LLMs are surprisingly good at debugging when they can see what's actually wrong. Without logs, they're guessing. And an LLM guessing at bugs is like a doctor diagnosing you over the phone while you refuse to describe your symptoms.

A bunch of server logs on my NextJS app

A bunch of server logs on my NextJS app

👁️ Visual feedback

For UI work, the LLM needs to see what it's building. Screenshots, recordings, or better yet, tools that let it view the running application. It doesn't have eyes. You are its eyes. When you ask for a layout change without showing the current state, the LLM is working blind. Show it the page, point to what's wrong, and the quality of fixes goes up dramatically. The pattern here is: if a human engineer would need to see something to do the job well, the LLM needs to see it too. A screenshot speaks a thousand words.

In the article A Practical Guide to Vibe Coding with Cursor I go into more details on tools (MCPs) and tactics you can use to save time when providing those 3 forms of context.

🧪 Rule 4: Test or Regret

Here's what I wish someone had told me earlier: write tests or pay later. The pattern is predictable. The LLM builds your feature. It works. You iterate, asking for changes and refinements. Each change has a small chance of breaking something else. After ten iterations, something definitely broke. You don't know what or where.

Bugs are fine and they are obvious: there's an error message, the page doesn't load, the button doesn't work. You see them and fix them. But regressions don't shout, they whisper. The payment processes but the confirmation email has the wrong amount. Everything appears to work until you realize it doesn't. A customer finds out in production and it costs you money or trust or both.

Tests are the only sane way to catch regressions. But which tests should you write?

There are three main types:

- Unit tests - Test individual functions or methods in isolation

- Integration tests - Test how different parts of your system work together (e.g., API endpoints, database operations, service layers)

- End-to-end tests (E2E) - Test complete user flows through the entire application

The best analogy I could find to describe those tests is with a car:

- Unit tests are like testing individual car parts on the workbench. Does the spark plug fire? Does the brake pad have enough friction? Each component by itself.

- Integration tests are like testing a function of it. Does the engine actually turn the transmission? Do the brakes communicate properly with the ABS system?

- E2E tests are like taking the car for an actual drive around the block. Starting it up, accelerating, braking, parking. Are we going from A to B safely?

Unless you're working on a massive codebase with millions of users, unit tests are usually overkill. End-to-end tests are expensive to maintain and brittle (they break easily when you change the UI).

Integration tests are often the sweet spot: they catch real problems without the overhead of unit tests or the maintenance burden of E2E tests. That said, unit tests can be valuable for critical business logic functions (like complex calculations or data transformations), and end-to-end tests make sense for mission-critical flows with stable UIs (like checkout or signup).

What makes a feature test-worthy though? Here are a few simple heuristics. Ask yourself:

- ✅ Does failure cost money? (payments, billing, refunds)

- ✅ Does failure lock someone out? (authentication, authorization, access control)

- ✅ Does failure lose data? (exports, backups, critical writes)

- ✅ Does failure break a third-party integration? (API calls, webhooks, external services)

- ✅ Ultimately: Would failure require a "We're sorry" email to customers?

If you answered yes to any of these, write integration tests. Everything else is negotiable.

Prioritize impact on the business over test coverage.

Examples: test your authentication flow, payment processing, data exports, and third-party API integrations. Don't test button colors or whether your error messages have the right punctuation.

Then actually run the test suite. Before every commit. Before every push. The LLM might have changed something three files away from what you were working on. The tests will catch it.

LLMs introduce regressions. So do humans. It's not a flaw, it's inevitable. When you're fixing one thing, you're not thinking about everything else that might break. The difference is that humans can be taught to check systematically, but LLMs optimize locally, fixing exactly what you asked about without considering the broader system. Tests are your safety net. They catch what you miss, what the LLM missed, and what neither of you could have predicted.

None of this is revolutionary. It's just engineering discipline applied to a new interface.

Specify before you build.

Break down complex tasks.

Provide relevant context.

Catch regressions with tests.

The tools changed. The principles didn't. Good engineering is good engineering, whether you're writing code yourself or prompting an AI to write it for you.

The difference is that now, the thinking part matters even more, because the "typing the code" part is done for you.

Written with ❤️ by a human (still)